This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

SOPA/PIPA and the MegaUpload shutdown

Published on Monday 17 January 2022

This week ten years ago, two major events happened in relation to the music industry’s long running war against online piracy.

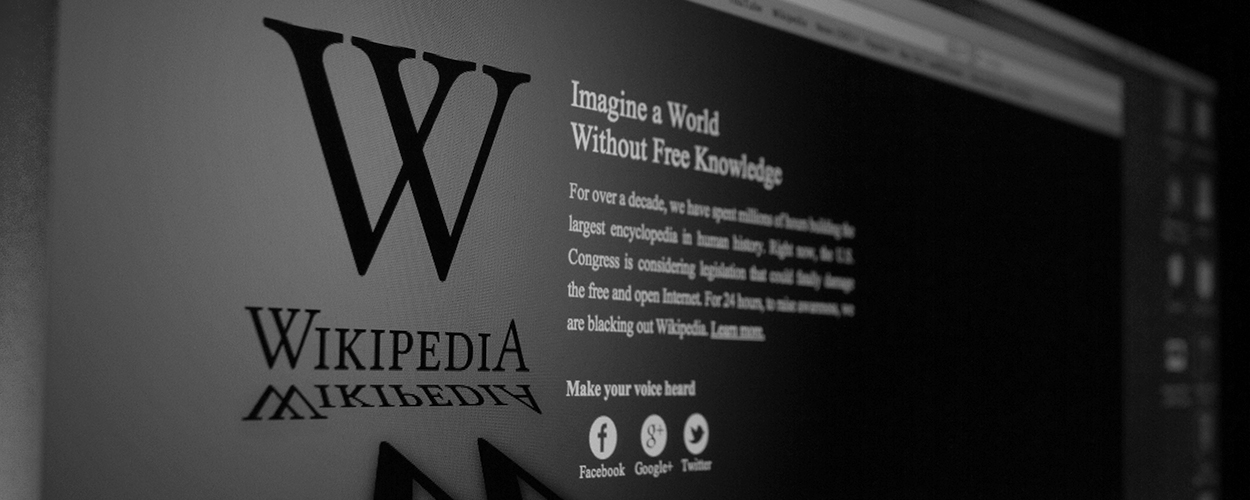

First, on 18 Jan 2012, Wikipedia basically blocked access to its English language service for 24 hours in protest at proposals then being considered in US Congress that would have introduced a web-blocking system into American copyright law. Those proposals were strongly supported by the American music and movie industries, but – following the Wikipedia blackout and other protests from the tech sector – they were quickly dropped.

Then, the following day, the US authorities – with support from the American music and movie industries – swooped on the popular file-transfer and video-sharing platform MegaUpload. The company’s entire operation was taken offline without any warning, its domains and servers were seized, and its senior management team – led by a certain Kim Dotcom – were arrested, facing charges of criminal copyright infringement.

Needless to say, it was a dramatic 48 hours for those of us who follow such things closely. For the music industry and its war on piracy, that was a major loss and a major win in very close succession.

But more importantly, it turns out, those two news stories together centred on what would become the music industry’s main priorities in terms of fighting piracy online: ie seeking web-blocking injunctions in court, while lobbying law-makers to reform the copyright safe harbour.

Although, while web-blocking became an anti-piracy tactic of choice in countries around the world, the events of 2012 meant it wasn’t an option for copyright owners in the US. And while the criminal case against MegaUpload was in theory a test of the copyright safe harbour, so far it has only actually tested the extradition treaty between the US and New Zealand.

But nevertheless, in the wider war against online piracy, over the next ten years the music industry put an awful lot of effort into web-blocking and safe harbour reform. Which was a change in direction compared to the first phase of the online piracy war that had been fought in the preceding decade.

LOTS OF LITIGATION AND SOME WARNING LETTERS

In the 2000s, during that first phase, there was an awful lot of lawsuits. Initially against the companies and organisations that provided P2P software and services, from Napster and Grokster, through Kazaa and Limewire, to the good old Pirate Bay. And then also against individual file-sharers who were uploading and downloading music without licence.

Although at the start there was some debate in some courts about the actual copyright liabilities of file-sharers and the makers of the technologies they employed, in the main the music industry won all the key battles. File-sharing other people’s music without permission was copyright infringement. And the providers of file-sharing software and services were also liable for contributory, authorising or – sometimes – even direct infringement.

However, there was a problem. Every time the music industry successfully sued a file-sharing company out of business, there was another service ready to take its place, which had often already taken over as the world’s file-sharing network of choice anyway.

Meanwhile, however many thousands of individual file-sharers the global music industry sued – and however much press coverage those lawsuits got – none of that seemed to deter anyone from downloading a load of free music and movies via file-sharing services.

By the late 2000s, the music industry had started to shift to an alternative strategy. It was decided that the internet service providers should be taking some responsibility for combatting piracy, possibly by sending out warning alerts to file-sharers, with the threat of penalties for any file-sharing customers that didn’t heed the warnings.

Understandably, few ISPs were keen to take on that role, which meant copyright law would likely need to force them to act. And when the UK Parliament started discussing the 2010 Digital Economy Act, the British music industry saw an opportunity to try and amend copyright law to that effect, forcing ISPs to start sending out warning alerts to their users.

Despite strong opposition from most ISPs, and so called ‘digital rights’ campaigners, an obligation of that kind was ultimately included in the 2010 DEA. Although it took a very long time for any warning letters to be sent out.

THE WEB-BLOCK PARTY

In fact, by the time those warning letters were being sent, the UK music industry had already decided to prioritise a different anti-piracy tactic – ironically a tactic overtly deprioritised by the Digital Economy Act.

And that tactic was web-blocking. The process of securing injunctions forcing ISPs to block their customers from accessing piracy sites. It was a test case in court in 2011 rather than any change to the law in 2010 that confirmed such injunctions were available in the UK.

Which meant that web-blocking was already underway over here by the time Wikipedia staged its big old headline-grabbing 24 hour blackout in protest of the web-block-enabling Stop Online Piracy Act and Protect IP Act that were then being considered in US Congress.

Amid claims that web-blocking would negatively impact on legit websites that inadvertently infringe copyright – like Wikipedia – American politicians dumped SOPA and PIPA and the web-blocking they would have introduced. And it has pretty much stayed that way ever since.

Which means that – while in the UK and elsewhere web-blocking has become routine and uncontroversial – in the US it’s generally still not an anti-piracy tactic available to copyright owners, with some nominal exceptions. Even though, it’s worth noting, rampant web-blocking in the UK has not negatively impacted on any legit websites like Wikipedia.

True, ISPs generally moan loudly whenever web-blocking is introduced in any one country for the first time. But once the web-blocks are being issued, most net firms fall in line, and some have even become active supporters of this particular anti-piracy approach.

REFORM THE SAFE HARBOUR!

Meanwhile, for much of the following decade, it was safe harbour reform rather than web-blocking that garnered all the controversy, especially around the negotiation of the 2019 EU Copyright Directive.

The copyright safe harbour is a legal principle that says that internet companies which unknowingly facilitate the copyright infringement of others cannot be held criminally or financially liable for that infringement.

Providing, that is, that those internet companies have systems in place to deal with and remove infringing content on their servers – and repeat infringers among their customer bases – if and when they are made aware of such things by a copyright owner.

If the MegaUpload case ever gets to an American courtroom, Dotcom et al are likely to say that their operation enjoyed safe harbour protection, just like its competitors Dropbox and YouTube. So if they were liable for all the music and movies being shared on their platform, Dropbox and YouTube were liable for any music and movies being shared via their respective networks too.

Prosecutors will argue that MegaUpload only paid lip service to its safe harbour obligations and that it actually actively encouraged users to share copyright infringing material. And Dotcom et al will presumably deny that.

But, as noted, the MegaUpload case still hasn’t got to an American courtroom for such safe harbour arguments to be had, with Dotcom and his former colleagues somehow still fighting extradition in New Zealand.

Nevertheless, elsewhere the music industry has worked hard to evolve the copyright safe harbour, through the courts in the US, and through lobbying efforts in Europe. And that has often involved going to battle with the kinds of legitimate internet businesses that MegaUpload was so keen to equate itself with – mainly ISPs in the US, and YouTube in Europe.

As we explain in this Building Trust white paper CMU produced with Friend MTS last year, as a result of that activity, how the copyright safe harbour works has evolved quite a bit over the last ten years. In the US as a result of precedents set in court. In Europe via the aforementioned EU directive.

WAS IT WORTH IT?

The other big change over the last ten years, of course, is the complete reversal of fortunes for the record industry.

In 2012 the recorded music business was at its lowest ebb after more than a decade of declining revenues. The rise of the iTunes Store had helped significantly slow that decline, but it hadn’t taken the sector back into growth.

And while the rise of Spotify and subscription streaming in general was already underway in 2012, it would be a few more years before the streaming boom would enable the record industry’s revenue revival.

Given it ultimately did, though, you might wonder whether all that work on web-blocking and safe harbour reform was really worth the effort.

After all, cynics might say, the web-blocks are pretty easy to circumvent. And the jury is still out on the tangible impact of safe harbour reform. Plus user-generated content services now want in-built music libraries to simplify the syncing of music, so can’t rely on the safe harbour any more anyway.

Although, as someone who was pretty critical of the music industry during that first phase of the piracy war in the 2000s, I think both web-blocking – providing it’s subject to judicial oversight – and safe harbour reform – when focused on removing ambiguities and loopholes – are sensible.

Neither are a panacea of course. And anti-piracy work only has value when the music industry is concurrently and constantly embracing – and making it easier to license and run – new kinds of music services.

But neither web-blocking nor safe harbour reform need to be as controversial as they were ten years ago – and have been at various points in the subsequent decade too – and both do have a role to play as the digital music market continues to evolve and expand.

MORE STUFF…

This Setlist Special from 2019 talks about how web-blocking became the music industry’s anti-piracy tactic of choice.

This Setlist Special from 2019 runs through the whole MegaUpload saga – well, up until 2019, but not a lot has happened since then.

This Setlist Special, also from 2019, looks at the music industry’s love hate relationship with YouTube as safe harbour reform became a priority.

To get up to speed on all the current streaming, copyright and music piracy trends, check out these upcoming CMU webinars.